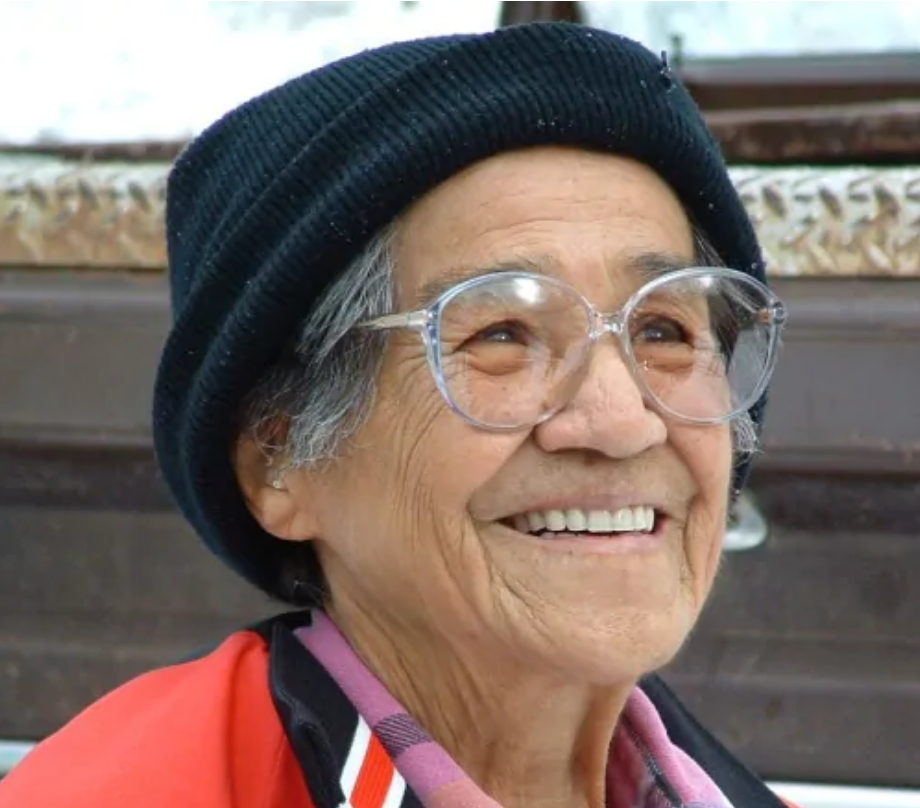

Annie Kruger was a firekeeper in a long line of people who were trained to use fire to take care of the land. (Don Gayton)

In the last several years we’ve witnessed growing intensity of fires around the world.

In the post below, Mourning a Disappearing World as Australia Burns, Jessica Friedmann in The Globe and Mail, January 2, 2020, writes:

“There is no doubt that the fires are growing more ferocious.

“Even without the changing climate, it would be inevitable; 250 years of land mismanagement have changed the way in which Australia’s bushland reacts to a spark.

“Before colonization, fire was managed with cultural burning, sometimes called fire-stick farming, which prevented vegetation build-up, germinated seed pods and regenerated the trees and grasses that need fire to grow new shoots.

“These burns rotated through a mosaic pattern, staggering the growth of eucalyptus and enriching the soil. These burns were slow, allowing time for animals to relocate and, most importantly, they were controlled.

“That changed after 1788. When the country was forcibly settled, large swaths of managed land were cleared to make way for livestock unsuited to an Australian environment.

“Cloven hooves ruined and degraded the soil; eucalyptus trees, with their oily trunks and flammable leaves, were left to grow thick and unattended at the fringes of clearings, building up undergrowth as dry as paper.

“When fire came, it didn’t come as part of a managed cycle, but ripped through, uncontrolled. The author of an 1851 Argus newspaper report, bewildered, describes the fire in Biblical terms:

“Connor’s farm, produce, and implements are utterly destroyed.

“On Robinson’s farm, four thousand bushels of wheat and one thousand bushels of oats, together with everything of value.

“From Costigan’s up to Robinson’s, this point presented nothing but black desolation.

“From the high range above, far as the eye could reach, the scene looked as though it had been swept by the wings of the destroying angel.”

Fire personnel try to extinguish a bush fire as it burns near homes on the outskirts of the town, Bilpin, Australia, Dec. 19, 2019.

****

In this post, Forget Smokey the Bear: How First Nation Fire Wisdom is Key to Megafire Prevention, Yvette Brend for CBC News Canada, July 17, 2017 says,

“The grandchildren of Annie Kruger remember her lighting an Export A Green cigarette, throwing on her logger’s jacket and heading out to set fires near Penticton, B.C.

Annie Kruger, firekeeper

“Before she died she was a firekeeper — as were generations before her in the Okanagan region of the province — and it was her job to use flames to purify the land by setting fire to berry bushes, hillsides and even mountains to renew growth and clear brush and create natural fireguards.

“‘Our family have been firekeepers for thousands of years,’ said Pierre Kruger, Annie’s son.

“Kruger cited several big fires he said his family started hundreds of years ago when lines of Kou-Skelowh people walked beating drums to warn wildlife before setting fire to what’s now called Sylix territory.

“‘We warned the birds and four-leggeds,’ he said. ‘My mother taught us every fire is like a snowflake — no two are alike.’

“Annie kept up the tradition until she died in 2003.

“By then, authorities had long cracked down on the practice, pushing fire prevention hard starting in the 1930s, in full-force after 1945. Fire became bad, something to battle or ban.

“Remember Smokey, the iconic bear who doused fire near forests?

“Fire prevention experts fear that those policies, launched decades ago, unwittingly created conditions that are now feeding the out-of-control wildfires plaguing California and Alberta — and, in recent weeks, some 240 blazes in B.C.

“Experts are urging provinces to adopt more Indigenous burning practices because the long crackdown on constructive burning has built up fodder for fires.

“Why burning curbs megafires

“In North America, fire suppression became the prevalent way of handling fire over the past century, to protect property, ranch lands and people.

“But the practice left dead trees, forest litter and aging forests to become prone to disease, such as pine beetle infestations, fostering the perfect ignition material for spot fires to spread and converge, experts say.

“‘It’s a setup for huge fires,’ says Mark Heathcott, a fire expert who managed Parks Canada’s controlled burns for more than 20 years.

“When smaller fires merge, they can create megafires so intense and so fast, they are unstoppable.

“These kind of fires are becoming more common in the U.S. — and Canada has seen a few, as well. In 2003, a lightning strike in the Okanagan started a fire that burned 25,000 hectares and forced 27,000 people from their homes near Peachland and Kelowna, B.C. In 2011, a forest fire raged into Slave Lake, Alta., forcing the evacuation of 7,000 people.

“Then in 2016, the monster Fort McMurray fire led to the evacuation of the city of 88,000, making it the largest fire in Alberta history.

“In California, four million hectares burned in 2015, setting records and sparking fire experts to blame overzealous firefighting, arguing the land needs some fire.

“Land craves fire

“In recent years, science has emerged to prove certain lands have always had fire.

“Researchers examining fire-scarred trees in western Canada discovered that boreal forests actually evolved in places like B.C.’s interior and parts of Alberta because they were scorched to the ground every 75 to 100 years in a patchwork pattern, Heathcott said.

“‘Forests have to be burnt to regenerate,’ he said. ‘It’s tough to suppress that forever. . .’

How much burning is needed?

“‘How big is B.C.? That’s how much should burn every 100 years,’ said Heathcott, who estimates that in every century prior to this one, most of our 95-million-hectare province burned.

“It’s not realistic to set fires on that scale in the 21st century, given that many forested areas are now in proximity to populated centres.

“And nobody is advocating going back in time, but proponents like Heathcott say say more burning is needed.

“In 2016, the Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resources conducted 59 controlled burns, described as ‘valuable training’ for staff.

“The exercises depended on weather, and often got called off.

“Officials are wary of the legal risk of an escaped fire, and few have long-term experience wrangling flame.

“Fire misunderstood

“So while prescribed burning is no longer a hanging offence like Kruger claims it was for a few of his people in the 1880s, it’s still underutilized say proponents.

“A handful of First Nations groups are working to revive the lost practice of fire-keeping, but it’s slow, said Pierre Kruger. ‘We have to re-educate people. None of our families’ fires ever got away, but people don’t understand fire anymore.’

“He says his grandmother’s view of the megafires of today would be simple: people forgot to use fire.”

Another link about cultural burning, Yes! Magazine: